How San Francisco’s Clean Drinking Water Destroyed The 2nd Yosemite

A cautionary tale about progress and preservation

During yesterday’s talk with the Pattiz brothers, Will brought up an early example of public land being stolen from the American people. Just like today, the argument back in the early 1900s was one of a supposed emergency need. And while people in San Francisco continue to benefit from the water and power provided by Hetch Hetchy today, much was also lost forever.

I originally wrote this story in 2014—one of the first as I began my journey into writing about the intersection of public lands and politics—so I figured the time might be right to revisit it. We’re about to see the largest sell off of public land in modern history.

Did you know Yosemite Valley used to have an identical twin? It was dammed in the early 1900s to provide San Francisco with water it relies on to this day, but recently, conservationists have been calling for its restoration.

This is the famous view of Yosemite from the tunnel. Photo: Don J Schulte/Creative Commons.

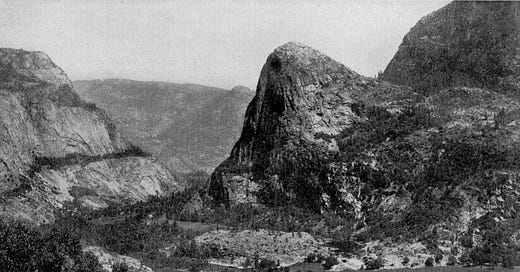

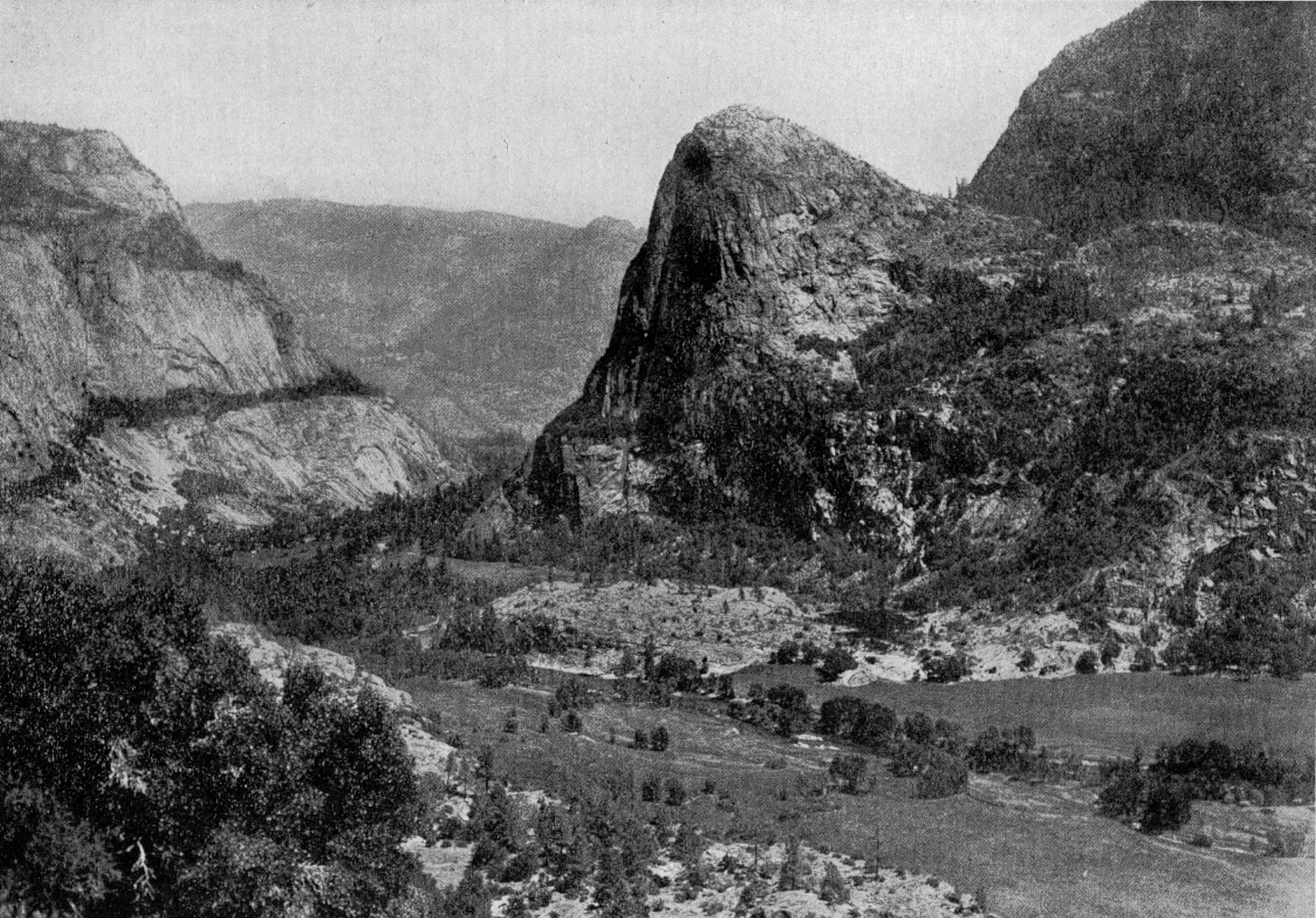

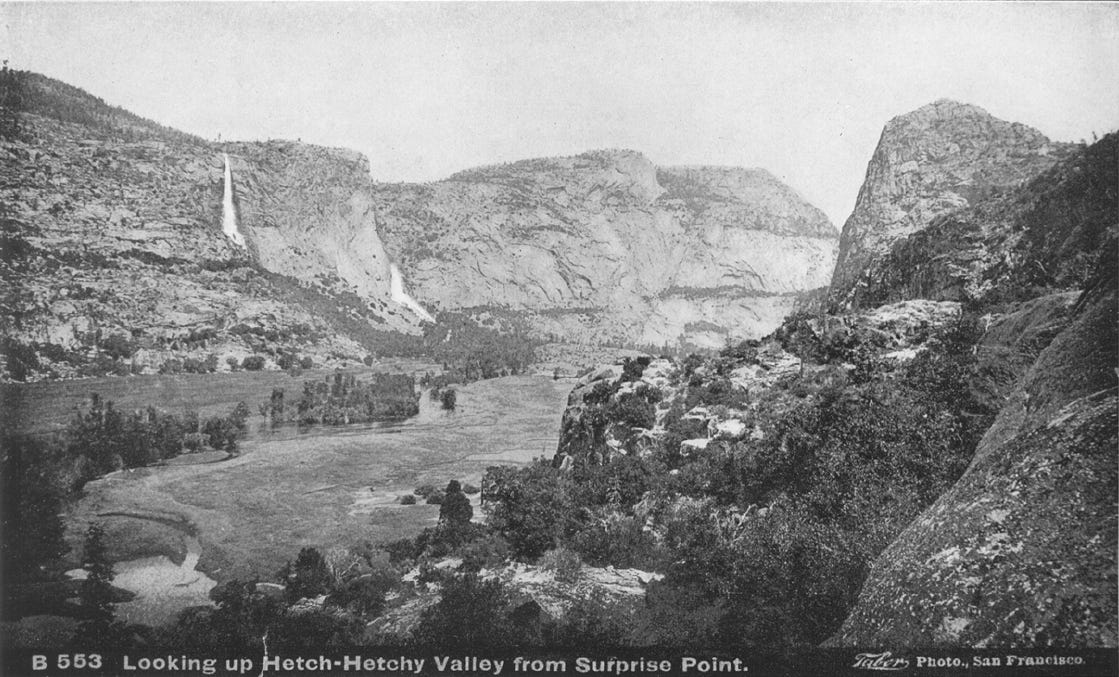

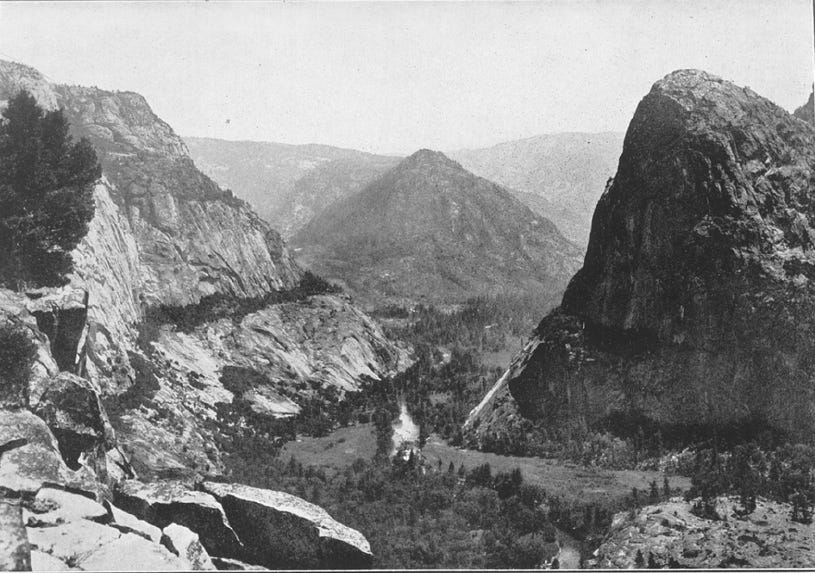

But, did you know that a near-identical valley used to lie just to Yosemite’s north? The Hetch Hetchy Valley also featured stunning rock formations and dramatic waterfalls. A huge rock spire called Kolana Rock protruded 5,772 feet from the south side of the valley floor, with the Hetch Hetchy Dome (6,197 feet) directly to the North. The locations of those two distinguishing features mimics that of Cathedral Rocks and El Capitan in Yosemite Valley. If you’ve seen Yosemite from Tunnel View (and you have, it’s one of the most photographed spots on earth), that’s what Hetch Hetchy used to look like.

This photo of Hetch Hetchy before the dam give you some appreciation of the comparison. Photo: Isaiah West Taber

John Muir famously described Hetch Hetchy as, “A wonderfully exact counterpart of the great Yosemite.”

Until, that is, 1919 when work began on the O’Shaughnessy Dam, which would eventually stand at 312 feet high and totally fill the Hetch Hetchy Valley with water.

The San Francisco Earthquake, Clean Water and Dirty Politics

At 5:12am on Wednesday, April 18, 1906 an earthquake of between 7.7 and 8.25 in magnitude struck San Francisco. The fires that broke out in its aftermath swept through the city, destroying 80 percent of it. A natural disaster so great that it’s remembered as one of the three worst in United States history, up there with the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 and Katrina.

The city’s water system — thought to be inadequate for decades — utterly failed and, if San Francisco was to rebuild itself, it needed something entirely new.

Using the Hetch Hetchy’s Tuolumne River as a water source for the city had been proposed as far back as 1850, but efforts to diver its water to the Bay Area had been frustrated first by competing water rights owned by municipalities closer to its source and then by the valley’s inclusion in Yosemite National Park when it was established in 1890.

The earthquake was the motivation needed for the Department of the Interior to reconsider the city’s access to Tolumne water and, the year following the quake, James Garfield granted San Francisco the right to develop the river.

It was apparent that Hetch Hetchy made a perfect site for a reservoir from the beginning. With steep valley walls and a narrow outlet on the west side, it could hold a huge amount of water for relatively minimal effort. At 3,812 feet in elevation, the valley was capable of supplying San Francisco with water via gravity, with the added potential for hydroelectric power generation as the aqueduct, pipes and tunnels fell towards the west.

These were the early days of wilderness conservation and any arguments to preserve the valley’s natural state were quickly superseded by progress. In 1913, Congress, along with President Woodrow Wilson, granted the city the right to flood the valley, but only under the condition that the power and water it provided could only be used for the public good, with no private profit derived.

Work on the Hetch Hetchy Project began in 1914 with the construction of The Hetch Hetchy Railroad, which would transport construction materials and crews to the eventual site of the dam. Work on the O’Shaughnessy Dam was then able to begin in 1919 and it was completed in 1923.

Before dam. Photo: Herbert W. Gleason

So far, so good. Construction of the 137-mile pipeline that would eventually carry the Hetch Hetchy’s water to San Francisco was able to begin, as was the construction of hydroelectric power stations and the lines they would use to transmit that power to the city.

After, damn. Photo: Justin Gaerlan/Creative Commons

Until 1925, when the city abruptly announced that it had run out of money to fund the project. Construction of the power lines inexplicably reached as far as the Pacific Gas & Electric’s newly constructed substation in Newark, California, just across the bay from San Francisco. Conveniently, PG&E had just installed a new high voltage line across the bay and it was announced that the company would temporarily take over the deliver of that power to the city, buying the power from it and selling it back to its citizens at a profit. Over the next decade, a National Park Service investigation found the arrangement to be illegal under the act that granted the city access to the Hetch Hetchy, but the temporary nature of the arrangement meant the Department of the Interior was unable to take action. PG&E spent over $200,000 defending its interests in eight legal challenges in San Francisco and the issue eventually went to the Supreme Court in 1941, where it was ruled illegal. But, the handover of power transmission dissolved into a political mess that continues to this day. Legal challenges to the situation began in 1941 and have been made as recently as 2012.

One of the largest and most successful gravity-fed and power-generating municipal water supply systems in the world today.

As it stands, it could be argued that PG&E continues to profit from Hetch Hetchy’s water and power in direct violation of the act of Congress that originally flooded the valley.

Conservation Efforts Then And Now

The Hetch Hetchy was not dammed without protest.

“Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man,” wrote father of conservation John Muir in 1912.

In fact, this issue was the first time a national audience weighed the virtues of progress versus the preservation of nature. Until that time, the prevailing view was that nature was something to be conquered by man and that its resources — oil, wood, water, animals, beauty — were essentially infinite. Hetch Hetchy was the beginning of a sea change in American attitudes on their relationship with nature and the beginning of a widespread conservation movement. It was the Sierra Club’s first major battle and fostered the creation of the National Parks Service, transferring management of the parks from the Forest Service (a resource management body) to the Parks Service (dedicated to preservation).

Hetch Hetchy was the touchstone moment in which the modern conservation movement spread into both the public consciousness and public policy and we have it to thank for the protection of the Sierra Nevada and other wild areas that exists to this day.

Muir argued that San Francisco’s water could just as easily be collected downstream on the Tolumne, in an area of less ecological import. That argument continues today, with a new movement dedicated to restoring the Hetch Hetchy Valley to its original glory.

A map of the water system as it exists today.

Restore Hetch Hetchy seeks to drain the valley, shift its water supply to the much larger Don Pedro Reservoir and restore the area’s diverse ecology. The dam would remain in place, too costly and too environmentally damaging to remove. They argue that Hetch Hetchy’s 360,000 acre-feet of water is now insignificant in the broader picture of California’s water supply and that transferring that capacity to Don Pedro would require only a 20-foot rise in that reservoir’s capacity. A study by the state Department of Water Resources estimated the cost of this project at between $3 and $10 billion.

That sounds expensive, until you factor in the regular maintenance required by such a vast system of infrastructure. Currently, a $4.6 billion project is underway to earthquake-proof some of the original pipeline. Another project, estimated to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars range is underway, replacing concrete tunnels damaged, wait for it, by the water’s purity. It’s so free of minerals that the water has been leeching them from the concrete tunnels it passes through shortly below the reservoir. Something that, nearly 100 years later, has pitted the concrete and weakened it.

The need for most of that maintenance would not be removed by draining the valley, but it does put the potentially $10 billion cost of the project in perspective. The Parks Service backs the plan and has studied its potential impact. The findings? If properly managed, “…the entire valley would appear much as it did before construction of the reservoir.”

An artist’s rendering of what Hetch Hetchy could look like post-restoration. Art: HetchHetchy.org

The Hetch Hetchy Today

As it stands, flooding the Hetch Hetchy has been far from an environmental disaster. It provides over 2 million residents of San Francisco with drinking water so clean, it’s one of the few cities in the nation not required to treat it. They do add a little chlorine just to be safe.

Hetch Hetchy water also powers thee major hydroelectric power stations, providing a clean, renewable energy source for California. Together, they generate 1.6 billion kilowatt hours of electricity each year or about 1/100th of the state’s total demand.

But what of the Valley? You can still visit it today, hiking a path that skirts the north side of the valley. Because it’s a source of drinking water, swimming and boating in the reservoir are prohibited, but the fishing is said to be good. Because much of its visual splendor has been lost, the area is also much less frequently visited than Yosemite Valley, with most hikers reporting seeing only five to 10 other humans there a day.

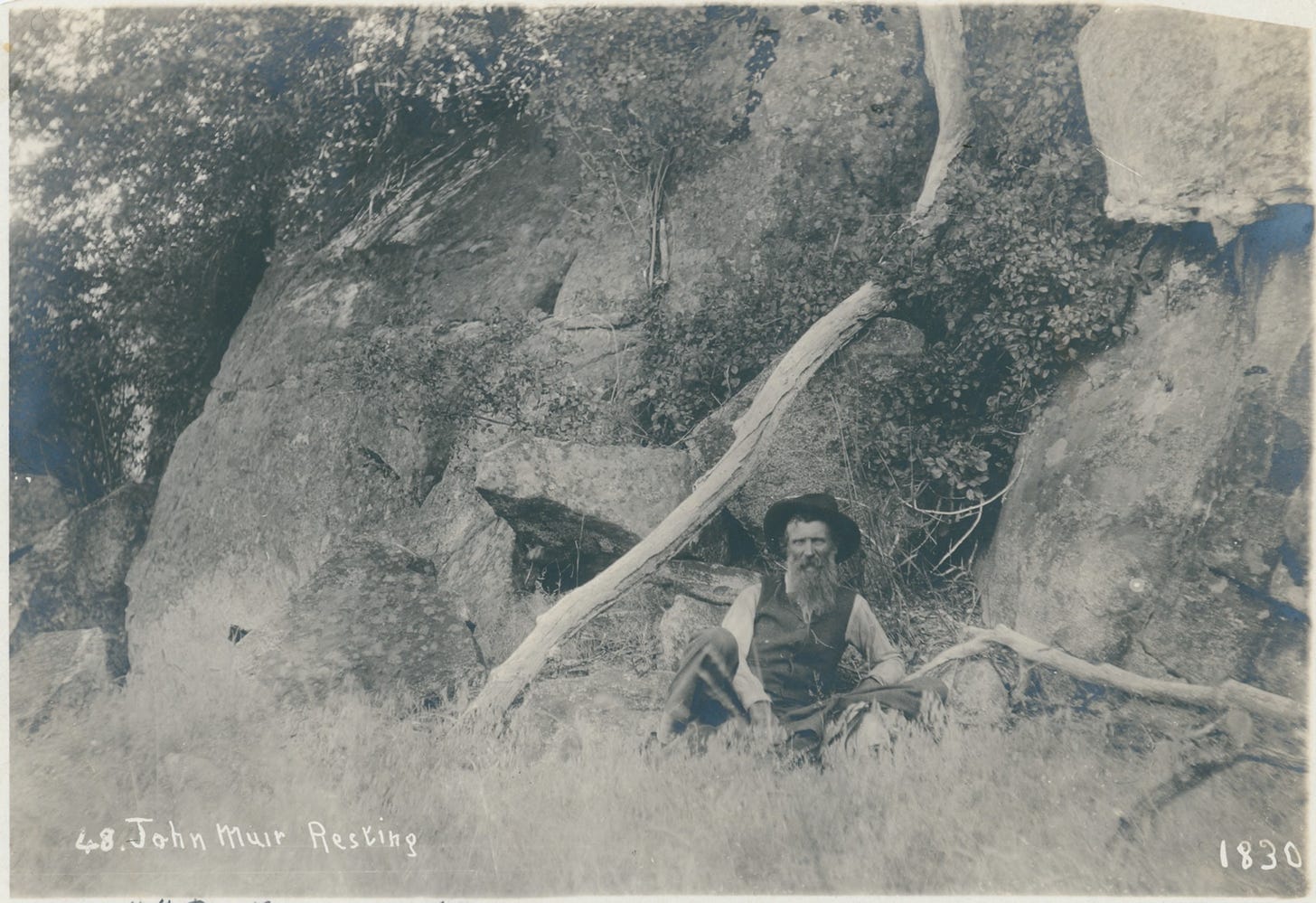

John Muir in Hetch Hetchy Valley. Photo: University of the Pacific

Top photo: Herbert W. Gleason

Wes Siler is your guide to leading a more exciting life outdoors. Upgrading to a paid subscription supports independent journalism and gives you personal access to his expertise and network, which he’ll use to help you plan trips, purchase gear, and solve problems. You can read more about what he’s doing on Substack through this link.

For what it's worth, not only SF, but many towns on the SF Peninsula get most if not all of their water from the Hetch Hetchy system.

As a life member of Sierra Club, I am aware of both the irony and hypocrisy, of using Hetch Hetchy water.

I would be interested in measurements of micro-plastics in both the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, and at the point-of-use (i.e., in my home) of this water source.

I look at the three great valleys of the Sierra Nevada -- Hetch Hetchy, Yosemite, and Kings Canyon -- and I see one sacrificed for water development, one sacrificed for commercial development, and one left nearly in its wilderness state. Is that a fair characterization? And, if so, is that a fair distribution of these resources? Rhetorical questions.

All that said, I do not foresee tearing down of the Hetch Hetchy dam, and relocating it downstream. Retaining the status quo seems to me to be least-bad, at this point in history. (Although I'm very aware of what's been happening on the Klamath.)

We did a series of double blind taste tests and people preferred East Bay and Marin water.

https://hetchhetchy.org/san-francisco-chronicle-surprising-results-for-hetch-hetchy-water-taste-test/