Cuts At National Park Service Aren’t About Efficiency

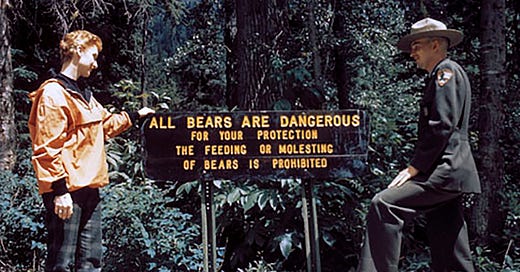

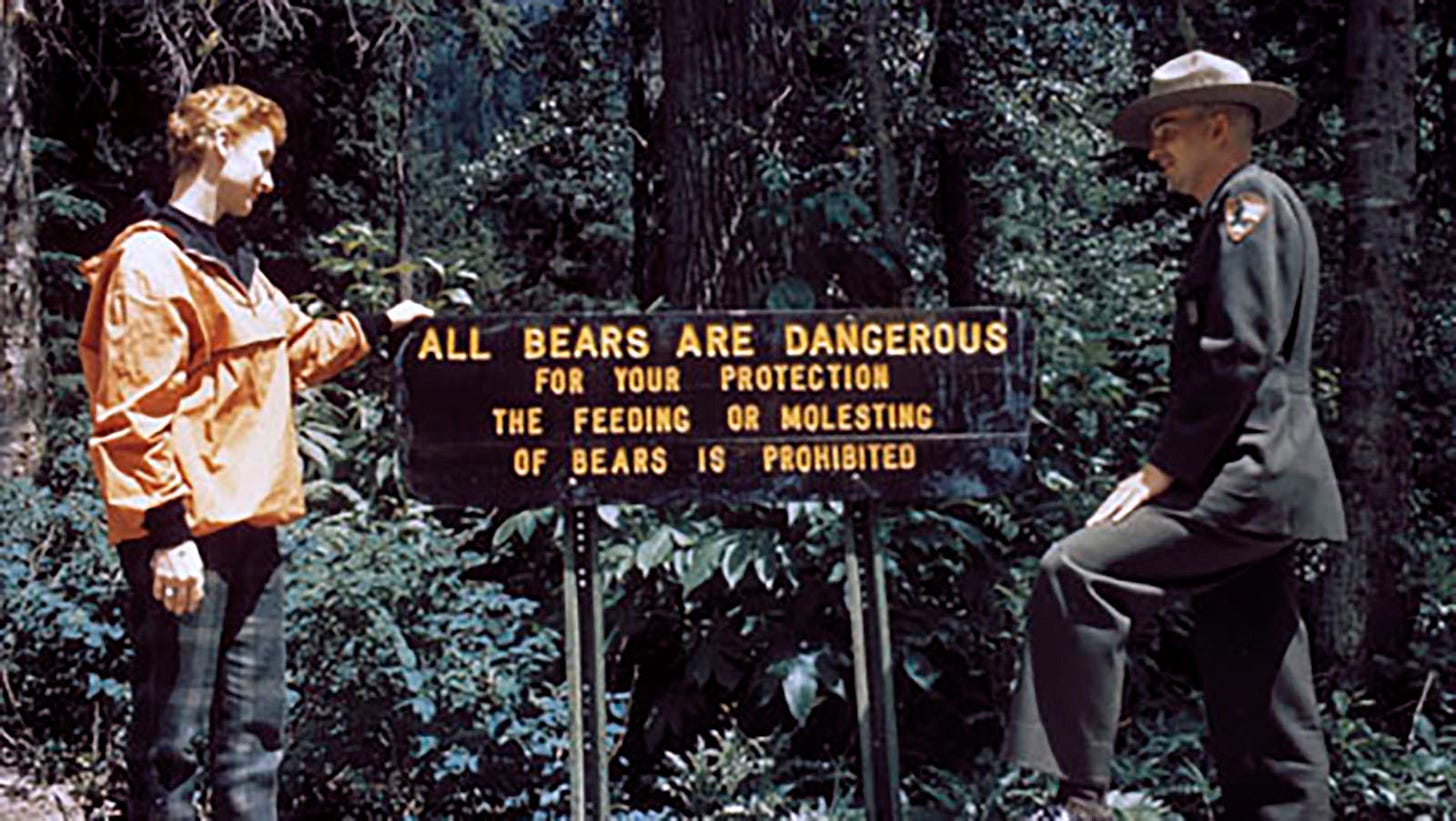

How firing 31 percent of the agency’s staff will cost taxpayers billions, imperil the nation’s natural treasures, and give you the runs

Last week, 1,000 full-time employees at the National Park Service were laid off. Contracts for the agency’s 7,500-strong seasonal workforce are in doubt. Together, that represents about 31 percent of the agency’s total workforce. The Trump administration claims its sweeping reductions in the federal workforce are being done in the name of “government efficiency,” but in National Parks, these cuts will end up costing the government more money than it saves, and will also leave you with a very upset tummy.

The cuts impact all 433 units that the park service manages, and firings have seemingly been done at random, impacting largely “probationary” staff—those who have been in their current positions for less than one or two years. That doesn’t necessarily mean those employees are new hires, workers who have transitioned from contract to full-time employment are included, as are ones who have transferred between departments within the agency.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Wes Siler’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.